“Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

You shall possess the good of the earth and sun, (there are millions of suns left,)

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand, nor look through the eyes of the dead, nor feed on the spectres in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from your self.”

Walt Whitman,Song of Myself

Do you enjoy poetry? No? Too precious, too abstract, too far from your daily life and its tough, quotidian concerns? Spoiled for you by heavy-handed teachers who insisted on analysing “AABBCC” rhyme schemes? Let me see if I can change your mind.

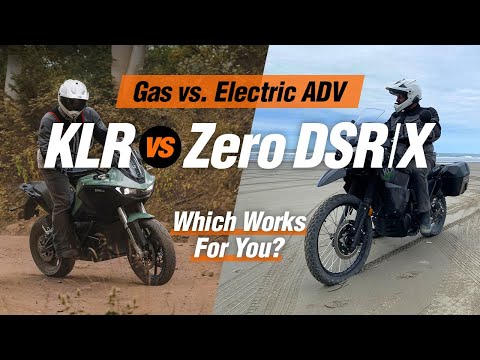

我对自己背诵诗歌当我骑。智慧h my voice, it’s safer than singing. I have been known to stop and pull out a poetry book to check the next line when my memory runs out. This is an excellent way of memorising entire poems. Motorcycling goes well with the rhythm of poetry. It can also benefit from poetry’s unique advantage: the ability to elevate stories, and convey emotions, that prose would either not be able to express at all or for which it would need many more, and lesser, words. Motorcycling is to poetry as driving is to prose.

It is easy to think of poetry being all about flowers and such. But there is a tougher kind.

Poems, like songs, which are poems set to music anyway, can lift or dash your mood, or they can comprehensively open your eyes. Here’s the beginning of the Iliad, one of the earliest major poems that we can recognize as such. It’s Homer, setting the stage for the siege of Troy.

“Sing, Goddess, Achilles’ rage, / Black and murderous, that cost the Greeks / Incalculable pain, pitched countless souls / Of heroes into Hades’ dark, / And left their bodies to rot as feasts / For dogs and birds, as Zeus’ will was done.”

This is not some prissy concern about daffodils or fainting maidens in flowered meadows. It is about death, and honor and dishonor among those whom Ulysses later calls “names” who will live in song and story for thousands of years.

Here Ulysses is again: Lord Tennyson, much later, has him say “I am become a name; for always roaming with a hungry heart. / Much have I seen and known…” No matter who the poet is, the message is the same: history will recall what we did, and how.

Chanting is a good way to learn poetry. And where better to chant than on a bike, where nobody can hear you?

Norse skalds knew the importance of music. They sang “Kine die, kinfolk die, / and last of all yourself. / This I know that never dies, / how dead men’s deeds are deemed.”

Shakespeare had the cadence right when, at Agincourt, he has Henry V ask his knights to “Dishonour not your mothers: now attest, / That those whom you call’d fathers did beget you. / Be copy now to men of grosser blood, / And teach them how to war.”

Mother Nature, a motorcycle and a poem to ponder — it doesn’t get much better.

Not that poetry is all war and honour in classical times. “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower / Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees / Is my destroyer,” wrote Dylan Thomas, the man whose command of the English language is equaled by none in recent years. Can you feel that force, the power of nature itself?

American poet Annie Finch emphasises that poetry is not just the words. To her, rhythm and especially metre are powerful tools to strengthen a poem’s effect. She says that “Poetry chants and incants; it excites and lulls… a poem engages rhyme and a regular pattern of accents (eg, Langston Hughes’s ‘Hold fast to dreams / For if dreams die / Life is a broken-winged bird / That cannot fly’). If you want to come to know yourself more fully – to learn the languages not only of your mind but also of your heart and body – metre can be a strong ally, in offering the key to a wordless code that underlies the surface meanings of words.”

She expresses this in one of her own poems when she writes “May language’s language, the silence that lies / Under each word, move me over and over, / Turning me, wondering, back to surprise.”

Oh all right, flowers do go well with (some) poetry. Not with Ginsberg, though.

Allen Ginsberg starts his poem “Howl” with the now classic words “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,” and doesn’t let up for 112 long lines in a style based on that of the transcendentalist Walt Whitman. Very different in the choice of tone, in his “Song of Myself” Whitman writes “I loafe and invite my soul, / I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.”

You will not find yourself in tune with every poet you read, but give a few of them another chance. You’ll have something more interesting to recite in your helmet than the lyrics of “Little Old Lady from Pasadena”. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

(Photos The Bear)