This is Part 3 in a series of stories Bill wrote about his trip through the Rockies on a Yamaha T7 put together by the crew at Overland Expo. See Part 1hereand Part 2here—Ed.

After thawing out my near-frozen carcass in Silverton, Colorado, following my campout at Eureka Lodge, I had two more days of riding to go.

第三天:西弗敦百万美元的高速公路Robert’s Cabin

The T7 was massive compared to this petite (but loud) Ducati 250 Scrambler. Photo: Bill Roberson

Warmed and revived by a hearty breakfast at the Kendall Mountain Cafe in Silverton, I rechecked the bike and gear and prepared for a day of riding that would be mostly on pavement. I headed for Ouray on Highway 550, better known as theMillion Dollar Highway。尽管MDH是一个铺有路面的道路(和一个很好的人that), it is an adventuresome byway nonetheless, with twisting 200-degree switchbacks, stop-the-car (or bike) viewpoints and tourism spots like the Animas Forks ghost town.

But I didn’t stop much except for some gas and simply enjoyed the ride, and lucked out as the early weekday traffic was light—and included a local vintage motorcycle club out taking their collectibles for a ride along the stunning road that snakes through canyons, along sheer cliffs and below towering peaks. Aspens and other trees were just beginning to turn for the fall, adding to the color palette.

Cool classics ply the Million Dollar Highway near Ouray, Colorado. Photo: Bill Roberson

Why the “million dollar” name? There are lots of stories, from some saying it cost a million dollars a mile to build the road back in the 1920s (not really true) to a legend that an early car driver said he wouldn’t drive the twisting road again for a million bucks (good story but who knows?). Fortunately, it’s not a toll road and in great condition, and I had good weather. Winter travelers should check the status of the road ahead of time.

The Million Dollar Highway has what seems like a million hairpin curves on it, and is somewhat popular with motorcycle riders. Photo: Bill Roberson

Soon enough I was in colorful Ouray, Colorado, and ticking along at walking speed through streets clogged with tourist traffic. After a gas stop outside of town, I headed east on Highway 50 at Montrose and enjoyed the twisting alpine stretch before picking up the 285 at Johnson Village. My destination? A spot I stumbled across online called Roberts Cabin. You canread the long history of the cabin herebut suffice to say the two-story structure was built in the late 1800s and was used as a residence, barn, blacksmith shop and stable.

Roberts Cabin isn’t hard to find and is a great spot to start the ride up Boreas Pass. Photo: Bill Roberson

Over the decades, it fell into disrepair but in 1993 it was restored to its original form with a few “modern” updates including a metal roof, some basic beds, and a wood stove. And… that’s about it. There’s no electricity, no running water, and no bathrooms (but there is a clean outhouse). You canreserve the cabinand I locked in a night’s stay as it dovetailed with my next dirt-riding destination, Boreas Pass.

Roberts Cabin and the T7 sit in silence under the Big Dipper. Photo: Bill Roberson

I arrived well after dark, my white/yellow pair of Ruby lights illuminating the small walking path to the cabin. You cannot drive a car or truck right up to the cabin, but a motorcycle? No problem. Combination locks secure the doors and window shutters, you get the digits with your paid reservation. The cabin, while rustic, sleeps five—or ten if two to a bed. You’ll need to bring bedding and pretty much anything else (water, food, TP), but not wood for the wood stove; a bundle is kindly provided by the Forest Service. There are also candles and a modicum of cooking utensils if you decide to cook something on the wood stove, and past renters have left behind some board games, cards and other bits (feel free to contribute). A large fire pit outside the front door was tempting but I was just too tired. I checked in with my partner for the night via my Garmin InReach and then shut off my phone.

No sound except the crackle of a wood stove can send you to naptime pretty quickly. Photo: Bill Roberson

I was tempted to crack open my laptop and do some work, but the fire in the wood stove warmed up the cabin interior quickly and I found myself just sitting in sweet silence and stillness on the thin futon by the wood stove as the wood crackled and popped. After a day of wind noise and in-helmet music on the T7, the near-silence and isolation was solace and soon enough I had drifted off to sleep on the futon. I woke up a couple of hours later, spider sense tingling, and sounds coming from the outside of the cabin. Scofflaws trying to make off with the T7? Unlikely. More likely: Forest critters looking for a snack. I opened the door to find the T7 as I had left it, and a sky full of stars overhead. The Big Dipper hung on the horizon over the cabin and I snapped some long-exposure photos (above) before heading back inside. I added a bit more wood to the fire before crawling into my sleeping bag on the single lower floor bed.

Day 4: Boreas Pass and Mount Evans

Light streamed in the windows of cabin as the sun crested the surrounding ridges, and I committed the rest of the wood to the fire to bring back the heat inside Roberts Cabin. A thin layer of frost coated the T7 and the ground, but the temperature rose above freezing fairly quickly. I had a breakfast of energy bars and other snacks, and repacked the Yamaha for the day’s long journey: Boreas Pass to Breckenridge, and then the climb up to the top of 14,000-foot Mt. Evans, made easy since a paved road wound all the way up to the summit.

Boreas Pass affords some good views as it gently winds uphill. Photo: Bill Roberson

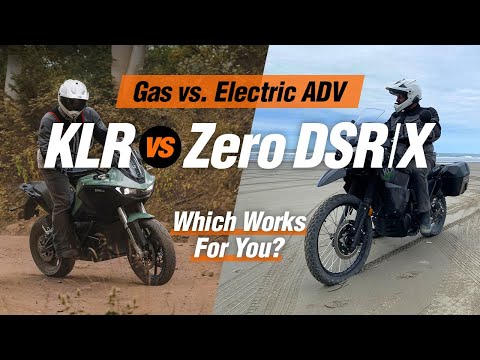

The road up to the summit of Mt. Evans is the highest elevation paved road in the United States (and one of the highest in the world overall), and while it may seem like cheating while on such an off-road capable motorcycle, I still wanted to give it a go. I would come to find out it wasn’t really “cheating” at all.

Picture hulking steam locomotives coming through this gap. Today it’s cars, trucks, motorbikes and bicycles. Photo: Bill Roberson

I took a few drone photos of the cabin and then started the T7 in the clear but chill morning air and began the climb up Boreas Pass, a graded and not-so-challenging dirt and gravel road that curls along old railroad routes to its 11,482 foot peak, where old railroad buildings sit amongst the meadow-like flanks of Boreas Peak. You can walk to the top of if you have the time and inclination (I had neither). From the top of the pass, the road winds gently down through lanes of tall aspens and other trees, as well as passages through rocky semi-tunnels blasted through to make way for the steam engines hauling timber and other material in centuries past.

Aspens, rock walls and camped out overlanders are common sights along Boreas Pass, an easy dirt road ride that ends in Breckenridge. Photo: Bill Roberson

跟踪早已过去,路点缀with campsites and turnouts sprinkled with overlanding campers. Tourists slowly climbed up the grade in Subarus and Land Rovers. Eventually, the dirt road of the pass reconnects to pavement high in the hills of Breckenridge. I descended through streets lined with multi-million dollar homes overlooking the scenic valley and ski city, still barren of snow while summer ebbed. It was a far cry from my silent overnight in the spare Roberts Cabin, but my temperament skews more to the comforts of a wood stove’s warmth than the decadence on display in Breck’s tony neighborhoods. To each their own.

不过,文明有一些优势,我enjoyed a hearty meal at the Blue River Bistro before resuming my journey. Back aboard the Yamaha, it was time to test yet another facet of the Ultimate Build: Highway riding, in order to reach Mt. Evans in a timely manner. Access to the road up to the summit is closed in the evening and you need tomake a reservation and buy a ticket to make the trip up, and to make time I’d need to ride a stretch of Interstate 70, which I had avoided until now. Tanked up with food, fuel, hydration and my Cardo Edge fully charged, I rolled on the power to join the 75 mph stream of semis, RVs, touring bikes, and other travelers on the mega-arterial.

Once up to speed, I activated the Atlas throttle lock for the first time, increased volume on my Cardo in-helmet speakers and reflected on the journey so far as the miles quickly ticked by. The Bridgestone Battlax Adventurecross tires, despite being more suited for dirt than pavement, tracked straight and predictably down the interstate, and the T7’s small windscreen punched just enough of a hole in the 75 mph airflow to make the highway transit comfortable. So far, the Ultimate T7 was proving to be ultimately capable.

I exited the 70 at Idaho Springs, and picked up tiny Colorado Road 103, which is a ride in and of itself as it winds towards Mt. Evans. At the entry gate, the temperature was in the mid-50s. While I show my ticket on my smartphone, I ask the Parks employee if she knows the temperature at the top of Mt. Evans. “It’s about 34 degrees,” she says. I dig out my winter gloves from the Mosko Moto panniers and put them in my jacket pockets for quick retrieval.

Some of the turns on the way up and down the mountain have good visibility. Many don’t. Photo: Bill Roberson

路上山的顶峰。埃文斯,县Road 5, begins typically enough, with broad lanes, fog lines, paved shoulders and a center stripe. But as the road ascends, the trees thin out and eventually disappear, and the road transitions back to its original form when it was built nearly 100 years ago with Ford Model Ts in mind, not Suburbans and Sprinter camper vans.

A traffic jam on the way up the hill. Not uncommon and I tiptoed the T7 past this foraging family. Photo: Bill Roberson

The centerline disappears in many stretches, as do the shoulders and fog lines, and I half expect to see Henry Ford hisself come around the next corner in a black open-top horseless carriage. The pavement is broken in places especially near the edges, potholes and rough patches are common, and in some sections the road heaves and drops in ways that could inspire roller coaster designers. It seems to be not more than ten feet wide in spots, and on many sections, the edge of the pavement terminates with no shoulder or guard rails to keep vehicles in play should they wander out of the lane, which is easy to do given the breathtaking scenery.

It was advisable to stay to far right part of the lane—despite hazards—heading into some corners, just in case an oncoming car or truck was hidden from view. Photo: Bill Roberson

Steep drops down craggy, rock-strewn mountainsides demand a driver’s and rider’s full attention. Modern DOT safety regs seem to not apply at many points as the tiny ribbon of pavement continues to ascend. Indeed, the road seems to bear out the git-‘er-done mentality of the time it was constructed, as reflected in a report to the then State Highway Department from those building the byway:

The use of heavy construction equipment was impracticable, and the contractor did practically all of the work with station gangs, who, with a shovel, hammer and drill, dynamite and determination, and copious amounts of Copenhagen snuff, literally forced the work through by hand, in spite of every obstacle.

Copenhagen must have really packed a punch at the time. On the T7, the many whoops, potholes and sloppy pavement patches are soaked up by the TracTive’s well-tuned suspenders, but that doesn’t mean I have an easy time of it; that this is a “paved” road seems more like an asterisk than accurate description. I lucked out and rode under best-possible conditions and was only grazed by a rain squall; anything else would have required steelier nerves to be sure and you might well surmise, closures are not unusual.

Sure, it’s a paved road, but I was happy to be on an ADV bike given its woeful condition. Photo: Bill Roberson

Turning through steep and blind 180-degree uphill 2nd-gear hairpin turns with sheer rock walls on one side and sheer drop-offs on the other (photo above) is unexpectedly nerve wracking, especially if a modern vehicle of any kind is coming the other way on the narrow pavement. Fortunately, traffic is very light, and my encounters with other drivers typically include slow, polite passes and a friendly wave or thumbs up. One car does go sprinting past me in an unsafe manner, the driver apparently mistaking the serpentine byway for some sort of semi-private racetrack. Watch out for the dips and deer, hot rod.

As you might expect, good weather affords amazing views from the 14,000 foot summit. Photo: Bill Roberson

I gain the summit after more than an hour of riding, which included some photo stops and a brief road closure due to a herd of deer wandering across the tarmac. In a sign of the times from way back when, a stately restaurant and cocktail bar awaited drivers at the summit, 14,130 feet up in the thin Colorado air. But a gas explosion partially leveled the place decades ago and the Parks department wisely chose not to rebuild it, instead installing some more practical public restrooms and preserving the unique architecture of the building’s remains as a sort of otherworldly lookout. Walking around at 14,000 and change is an odd experience as you can be both above some clouds but below others.

I lucked out on the weather, with this squall just missing the summit. Photo: Bill Roberson

For ambitious visitors not already wheezing from the altitude, a short trail from the parking lot through basalt talus leads to the actual 14,264 foot summit of Mt. Evans, which gives amazing views in all directions, provided the summit is not socked in with clouds or fog or snow storms. On my visit, the skies were mostly clear, with said squall passing nearby but not raining (or snowing) much on the route or summit. The temperature on the T7’s display reads 34 degrees as I saddle up for the trip down.

重新加入CR103,小郡路现在看起来ke a superhighway in comparison to the pockmarked ribbon up Mt. Evans. I head east towards Evergreen where I’ve booked a small A-frame cabin, but in my climb up to the top of Mt. Evans, I’ve overlooked an important necessity: gasoline. I had fueled up in the morning but the long blast down the Interstate at close to 80 mph and the long, slow slog up through the ever-thinning atmosphere has resulted in rather poor mileage, and with the tripmeter reading almost 150 miles, I’ve got one tick remaining on the fuel gauge. And it’s blinking. I click the gearbox to 6th and flow the T7 through the endless curves on the 103 while thankfully heading downhill, but eventually, the P-twin sputters and begins pushing nothing but air through the cylinders, and I am still high in the mountains and many, many miles from any gas station. I coast to the shoulder and uncork the two gas canisters that have been riding along for the trip on the back of the Mosko Moto pannier and pour 1500 ml of fuel into the tank.

The T7 gets good gas mileage, but no tank is bottomless. I had to activate Plan B to make it into town. Photo: Bill Roberson

This puts the tick back on the gas gauge and I continue my unhurried 6th-gear off-idle descent toward Evergreen. Once the 103 meets up with Highway 74, I quickly find a gas station and top off.

But while nibbling on some fine gas station cuisine, my phone reconnects to cell service and begins to buzz and beep with incoming emails and texts, including one from the operator of the A-frame bungalow I was going to stay in that night. Apparently a plumbing emergency has rendered it uninhabitable, and they sincerely apologize and have refunded my money. Great. For an hour, I poke at my phone, searching for another suitable spot and but find most everything booked, too expensive, too far away or all three. I finally find a room at a generic corporate motel but it’s all the way back in Loveland, tomorrow’s destination and the end of the trail as it were. I had planned to take the scenic route there instead of the boring interstate, and with the day’s light beginning to fade, I decide to take the scenic route anyway, as the Google traffic map on the most direct route is far too colorful and I’m just not quite ready to re-immerse into Traffic Hell just yet.

It had been pretty much all trees, road, rocks and sky until this tunnel, which emptied out into the suburbs near Loveland. Photo: Bill Roberson

I retrace part of CR74 heading north and connect to CR6, which traces through canyons and foothills at the base of the Rockies. To my right, the glow of the Denver megalopolis is a carpet of lights and highways. To the left, the Ruby aux lights illuminate the sheer rock walls as I trace along through canyons and intersections, some deserted, some busy with traffic. Traffic thins out on CR119 and eventually I join CR72 and begin to descend back towards Loveland, a bit hangry and disappointed that my trip is ending with a ride through clearly beautiful country solely illuminated by the bright but dimmable Ruby aux lights, which I have set for maximum firepower.

I’m clearly missing out on the true scale and grandeur I would have seen had I ridden through the passage in daylight. I soothe my disappointment with a heap of comfort food at Smokin’ Dave’s BBQ and Brew in Lyons before making the last descent through suburban tract homes and coiffed farm fields towards Loveland. At the midsize Average Corporate Lodging Facility, I check into my tiny but comfortable room, unload the T7 and soak in a warm-but-not-very-hot hot tub. I give thanks for an eventful but safely completed solo ride on some of the most amazing roads I’ve encountered so far in my short chapter of ADV riding, a trip made all the better by a professionally prepared Yamaha Ténéré 700 packed to the gills with gear that not only works but raises the game of both the bike and rider. My thanks again to Eva Rupert and her team at Overland Expo.

The photo ops on this trip were endless. If you get a chance to ride the Rockies, don’t pass it up, and take as long as you need to. I’ll be back for more. Photo: Bill Roberson

They say that if everything goes according to plan on a trip or adventure, it quickly fades from memory. Fortunately, I have many photos and some video to remember my too-brief Colorado Rockies transit, and a torn knee on my riding pants to remind me that good gear makes a key difference when things go south. And the Ultimate Build T7? I can’t think of what I would change (although Yamaha hasmade a few key changes for 2023 already). The excellent TracTive rear shock and front fork internals plus the additional 25 mm of travel made the going if not easier, certainly more capable than a stock setup, and the Bridgestone Battlax Adventurecross AX41 tires proved their worth on every surface. The Mosko Moto soft bags lived up to their reputation for toughness and capacity, carrying all my gear with room to spare.

Many thanks to our friends at Overland Expo for providing time aboard the Yamaha T7 Ultimate Build for this story. Photo: Bill Roberson

In fact, everything Eva Rupert specified for this build worked as designed, saving the bike from damage during a crash and keeping me moving forward on any surface from superslab to the rocky challenges of Cinnamon Pass. Yamaha has an excellent middleweight in the T7; its popularity is well deserved. But Eva’s upgrades made it even more capable and comfortable, especially for a rider still fairly new to wandering far from the traction of pavement. The bike was fun to ride, but more importantly, it was comfortable and manageable over the long haul, and forgiving of my mistakes. You can’t ask for much more than that in an adventure bike. The sweet spot indeed.

Overland Expo Yamaha Ténéré 700 Ultimate Bike Build Features:

TracTive X-TREME suspension+25mm F/R plus fork rebuild. A big difference maker.

Bridgestone Battlax Adventurecross AX41tires: Tenacious in the dirt and surprisingly responsive on pavement.

Aclim8 Kombar Titanium ProThis fine bit of kit was lost by a rider who had the T7 before my trip. Pity as it looked amazing.

Bark Buster handlebar guardsWorth every nickel in a crash.

Mosko Moto bags: Nomax tank bag, Backcountry 25 Panniers, Backcountry 30 Duffel, all built to withstand the apocalypse. The tank bag also features a hydration cell.

AltRider:bar risers, footpegs, clutch arm extension, water pump guard, brake pedal, high front fender, radiator guard. Stock is good. These upgrades are much better.

Outback Motortek: Tail Tidy, Center Stand, Ultimate Adventure Combo (Crash bars, bash plate, Luggage system: rear rack, luggage bars). Because a simple crash should not ruin your ride.

RAM Mountsphone holder/Zoleo mount. Flexible mounts – until you lock it down.

Taco Mototopo wrap. Make your bike look like how you want it to look.

Atlas Throttle LockOld skool cruise control, only better.

SBV Tool KitCheap? No. Value when it’s saving your butt? Priceless.

RUBY Moto R4 LightsBright LED jewels for your bike.

Zoleo GPS trackerFor when you’ve fallen and can’t get back up.

Doubletake MirrorsNOW you can see past your elbows.

Bill’s Riding Gear:

Rev’IT ApparelJacket and pants that look good and protect good, too.

TCX Infinity 3 Mid WP BootsWaterproof, and you can walk in them for miles (trust me).

Adventure Spec Dirt glovesLight, tough, breathable. And tough.

Bell MX-9 Adventure MIPS Helmetwith ProTint Adventure Shield. Comfortable, affordable, effective. Spring for the ProTint shield, too.

Tifosi SunglassesAffordable, tough and made to order.

Garmin InReach Satellite ComsI’m pretty sure texting via satellite is some sort of magic.

Butler Maps Colorado mapMaps specifically for motorcycle rides made by motorcycle riders.

Loop earplugsThey look different because they work better.

Leatherman Free P4multitool. Because: Pliers and stuff in your pocket.

Insta360 RS 360-degree cameraRelive your ride – from any angle.

Cardo PackTalk Edgehelmet comms. Tunes, talk and directions in your ears via JBL speakers.

Sea to Summit Alto TR1 tent。$12.80 an ounce and worth it.

Apple iPhone 13 ProAlmost all of the photos for this story – including the night photos – were shot with it.

Canon Powershot Zoomcamera. It’s like a little pocket telescope that takes photos, too.