Live long enough and you’ll meet people who confound expectation. Salt-of-the-earth farmers and semi-hermit backwoods dwellers who exude the wisdom of Walter Benjamin. And, conversely, self-proclaimed thinkers with less self-awareness than a bullfrog. Many people are more than what they first seem; just as many are less than what their intellect or experience would initially suggest.

Hands-down, the best storyteller I’ve heard is my late father’s youngest brother. He can tell a tale of going for take-out coffee that can hold a room rapt. And, like all good showmen, his timing is unpredictably flawless—my uncle is as expert at pacing a story as Willie Nelson is at phrasing a lyric behind the beat. Now the unexpected; my uncle stutters. Badly. But through wit, charisma, and sheer force of personality, he turned a liability into an asset. His stories progress in the non-linear fashion of a motorcycle ridden through a forest of downed trees. When he runs into a linguistic roadblock, he detours until he unearths language he can vocalize.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that devices designed by man can be just as beguiling as men themselves. This past Friday morning a large cardboard box arrived on our doorstep. In it were two high-backed barstools designed in the 1950s (that remain in continuous production) by the husband-and-wife design duo of Charles and Ray Eames. With tubular metal bases and a seat made of molded fiberglass, the chairs remain perpetually modern despite their 70-odd years of existence. And they’re unexpectedly comfortable. It’s these surprises that captivate and confound, and in motorcycling, I’ve never found a more perplexing duo than Harley-Davidson and Moto Guzzi.

When I first threw a leg over a Harley, I didn’t know what to expect. While the lifestyle bunkum that surrounds Harley borders on the grotesque, in the end it’s just a motorcycle like any other, with strengths and weaknesses. And a longtime guilty pleasure of mine, so help me, is 1970s choppers. Blame it on growing up in a lunch-bucket town where every fourth motorcycle was ridden by an Outlaw or Satan’s Choice clubber. Some might call it imprinting. My mother claimed it scarred me for life.

The Low Rider gleamed in the parking lot and made my road racing boots and full-face Shoei appear absurd overkill. Within a block I’d diagnosed that the fork had been assembled without oil. I knew because I’d also forgotten the oil when I’d rebuilt the fork on my own bike that very spring. I U-turned (and nearly crashed because I overestimated the footpeg-to-ground clearance) and returned the Harley. A technician test rode the bike, looked at me dismissively, and said the bike was fine. That’s how they all handled, he said. Who was I to disagree?

Despite its handling (think ’70s Coupe de Ville with 50-year-old shocks), I did my best to cuddle up to the Harley. It was slow, heavy, the gearchange was as elegant as shifting a John Deere, and the handgrips were like grabbing the business end of a baseball bat. But at its sweet-spot speed (about 40 mph), it was like riding a vibrating chair, the kind advertised on late night infomercials. The Low Rider made me so relaxed—and this is not an exaggeration—that I nearly fell asleep while riding it. Twice. I really wanted to like the Harley, if only to aggravate friends who believe it the two-wheeled antichrist.

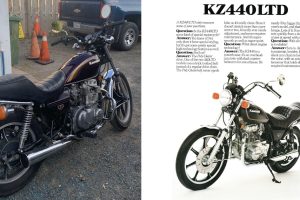

But there was one thing about the Low Rider—and this extends to every modern-ish Harley I’ve ridden (excepting models with footboards) that made it problematic. Whether in front-mount or mid-mount footpeg configuration, the peg location caused me excruciating pain, of a kind I’ve not experienced on any other style or brand of motorcycle. Within 50 miles my hips ached as if some unruly force had reached down from the heavens and tried to rip my legs off. Not even the V8-powered Boss Hoss put me in this kind of pain.

I was perplexed. In profile, the Low Rider’s riding position didn’t seem so extreme. My feet were neither thrust straight ahead into tomorrow nor unduly tucked beneath the buttocks. It was only when viewing the bike from overhead that the root of my malaise became apparent. The left peg had to clear the massive primary drive and the right peg the exhaust pipes. Allied to a seat height that made an ottoman appear lofty, the combination was evil. A month later, I rode a Sportster that put me in the same misery. Could it be that during the design process Harley-Davidson forgot its riders have legs?

When my neighbor, a man in his late 50s, told me he’d determined his lifelong love of BMW twins had been time misspent, my jaw flopped open. Henry, I’d believed, had stepped from the womb wearing a waxed cotton Belstaff jacket with a toolkit roll in the pocket. Indeed, Henry was such a model of self-sufficiency that no contractor ever entered his house. No electrician, plumber or roofer. He trimmed every errant blade of grass with unrelentingly efficiency. I’d never doubted that, had it been necessary, he could have performed the C-section for his own birth with the simple tools in his kit. If ever a man was destined to ride a BMW twin, it was Henry. But no longer. Henry had ridden a Moto Guzzi and was smitten. Not long after, I rode a Moto Guzzi for the first time. And, dammit, wasn’t Henry right—this was a motorcycle to fall in love with.

It was an 1,100 cc Breva, a motorcycle that could not be considered attractive. It was as if the hard-edged, brutal beauty of a 1970s Guzzi LeMans had been left too close to the fire and partially melted. I touched the bodywork with trepidation, expecting it to be warm and sticky. Mercifully, it was neither. And then I rode it. And laughed out loud. For a long time.

Guzzi,我意识到,我希望拖ey would have been. As soon as the revs rose the tremors disappeared and the Guzzi had the countenance of an old horse that would deliver you to the far side of the pasture at a speed that suited the old horse. The intake honk sounded like a draining bathtub and the exhaust note burbled pleasantly. And no matter how hard you rode, license-losing speeds never appeared on the speedo—you were always 20 mph over the limit, no more.

Whereas Harleys have the heavy metal appeal of industrial equipment (a backhoe, an air compressor, a log-splitter), a Guzzi has the same awkward playfulness of the 185-pound Newfoundland dog my wife once owned. Bubba clogged hallways, drooled uncontrollably, flopped in the dirt and rolled his tongue into the mud. He was a gentle giant with perpetually sad eyes. Hustling a Harley with any degree of urgency felt like work. But the Guzzi remained fun even as you thrashed it to near death.

Today, Moto Guzzi, having just celebrated its centenary year, limps on with a three-model range and one foot in the grave. Had it not been for the teasing of the all-new, yet-to-be manufactured V100 Mandello, it would not have been a stretch to suggest Guzzi was about to step into the grave with the second foot.

European motorcycle companies are not as idiosyncratic as they once were. Compare early KTM 950 Adventures with today’s Adventures. Or early Multistradas with current Multistradas. Or any old BMW with any new BMW. As we’re repeatedly reminded, the world is getting smaller. Moto Guzzi is one of the few brands left that didn’t get the message. They do their own thing, at their own pace. And while it’s likely not sound business practice to do so, I admire them for holding firm in a world swirling with change.